Biodiversity

Mindset of Change

Oh, What a World by Kacey Musgraves

Got a good headspace? Off we go.

“Of an inanimate being, like a table, we say “What is it?” And we answer Dopwen yewe. Table it is. But of apple, we must say, “Who is that being?” And reply Mshimin yawe. Apple that being is.

Yawe— the animate to be. I am, you are, s/he is. To speak of those possessed with life and spirit we must say yawe. By what linguistic confluence do Yahweh of the Old Testament and yawe of the New World both fall from the mouths of the reverent? Isn’t this just what it means, to be, to have the breath of life within, to be the offspring of creation. The language reminds us, in every sentence, of our kinship with all of the animate world.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

Biodiversity is such a poor word to describe the richness of the natural world. It somehow reduces our immense living heritage, an active communion in which we were meant to participate, into a resource that can be harvested and consumed, and perhaps restored. It freezes all of evolution into a snapshot that we can measure for our own purposes.

Pretty pathetic to be honest. But, it will have to do for now. I am no Native American poet-shaman to be able to convey the meaning of life so effortlessly. And while it is true that biodiversity represents many different species - the incredible flora, fauna, and fungi of planet Earth - it is even more important that it represents their relationships with each other and in maintaining ecosystems. Ecosystems whose loss or disruption greatly affects humanity, our comfort, our safety, and our future.

The salmon, the grizzly bear, and the spruce work together to create the richness of the forests of the northern pacific (adfg.alaska.gov). Mangroves, manatees, seagrass, oysters, and coral work together to maintain the coastlines in Florida and north east Mexico (amnh.org). Wolves, cougar, bison and deer provide balance to the prairie lands of middle America (wdfw.wa.gov). Mycorrhizal fungi, conifers and aspen work together to restore old mining sites (plantsciences.montana.edu).

In every ecosystem, balance is found by the presence of multiple species of plants and animals, some of whom we may not even be aware of. When humans overfish the salmon, we do damage to the grizzlies and the forests, which in turn affect the salmon further. When we remove the mangrove forests and kill the manatee, we open up our coastlines to greater storm surges, causing damage to human lives and homes. When we remove wolves from the food chain in Yellowstone, we let the deer and bison overgraze, causing erosion and flooding. If we destroy the ancient partnerships of aspen and fungi we may lose opportunity to learn how to fix our own destruction from strip mining.

Ecosystems work in complex cycles, species interconnected and actions affecting one affecting all. This can make them incredibly resilient, because parts of the cycle can support others, but it also makes them vulnerable to disturbance from multiple sides. And it often means they have tipping points. Tipping points occur when enough essential elements of an ecosystem have been affected that the system as a whole cannot recover in the same way. Maybe an invasive species finds opportunity to come in, or the landscape fundamentally changes such that the original occupants cannot return without intervention.

In 2019, only 23% of world land mass, in only five countries, was still wild, and only 13% of the ocean (theconversation.com). In 2023, 48% of known species were in decline. Yet, it is estimated that 80% of species on Earth have yet to be discovered and named (mongabay.com). The Amazon rainforest alone has already yielded numerous plant species that form the basis of medicines, including "the Vinca alkaloids which helped to make pediatric leukemia and Hodgkin's lymphoma curable" (onlinelibrary.wiley.com). Even if the only value we assign to biodiversity is what it can give to human beings, this is still an incredible loss - a vanishing opportunity.

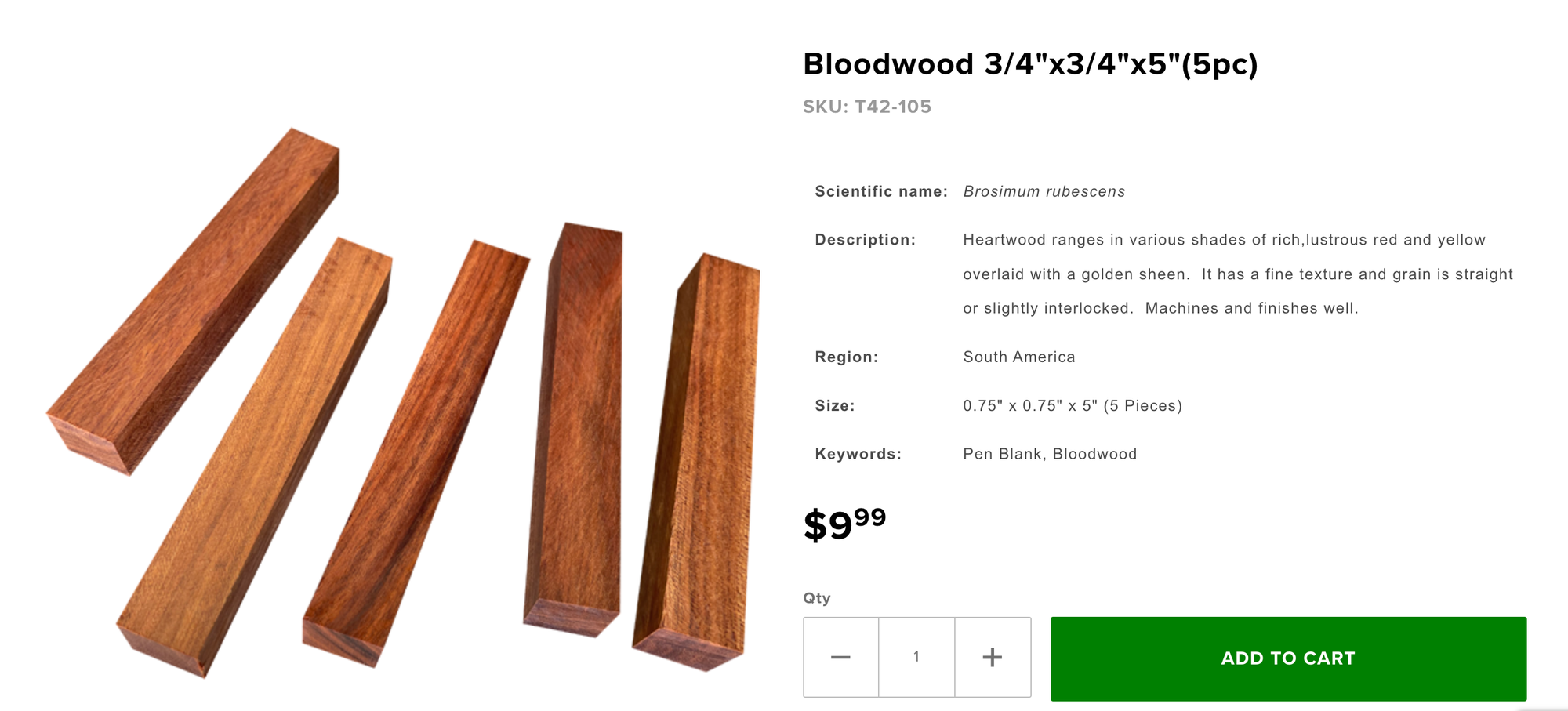

Why are we destroying the Amazon Rainforest - and so many other ecosystems - at such an incredible rate (time.com)? Primarily to make space for farming, particularly cattle and livestock feed, to satisfy the demand for beef. In addition, lumber is a valuable commodity, due to the demand for precious hard woods in the US, Europe and China (news.mongabay.com).

The same is happening around the world, in Madagascar, in Indonesia, the Philippines, the Congo (ourworldindata.org) (earthjournalism.net). Local populations, often to satisfy foreign demand for their resources, gut their own natural treasures.

In addition to converting natural habitats into farm land, climate change causes wildfires and flooding. Temperature change can also be deadly to more fragile ecosystems (nature.com). Our natural heritage is under immense pressure and has been for decades. Many scientists are worried that we are at the tipping point (nature.com). Its hard not to be alarmed. We should be alarmed. But at the same time, we should not be paralyzed. Nature is incredibly resilient, and if we change our behavior, much can be recovered.

Local Biodiversity

The Amazon Rainforest may be the poster child of biodiversity, but in fact, biodiversity is everywhere. It surrounds us. In fact, the US has some of the richest biodiversity, because the country spans so many different types of habitat, from mountains to prairies, desert to everglades. Historically, we also have a pretty progressive approach to preservation and conservation due to our National Parks (The National Parks, documentary by Ken Burns). However, we are also a country that has leaned heavily into monoculture farming, which has caused a number of issues, from water pollution to the depletion of nutrients in our food (jstor.org, Frank Uekoetter).

In historical Western agricultural tradition, crop rotation was essential to maintaining the health of the soil. In Year 1, you planted corn in Field 1 and beans in Field 2. Then in Year 2, you rotated them. You might also let chickens roam around to take care of excess bugs. In historical indigenous agricultural tradition, you planted the beans and corn together with squash in the Three Sisters technique. The beans climbed the corn and the squash protected the roots from pests. In both traditions, nutrients were returned to the soil, creating more nutritious crops.

Today, we practice monoculture farming, planting the same crop over and over, using chemicals to 'fix' the soil and pesticides to protect against bugs. The runoff from these chemicals pollutes the water table, eventually running into the ocean and causing algae blooms that wash up on beaches. Pesticides have dire consequences for bees and other pollinators. One has only to drive through Iowa in the summer, and see field after identical field of corn, eerily silent of birds and bees, to realize that something is amiss.

"Restorative agriculture" is starting to make a comeback though, as is the creation of micro-habitats, gardens and small urban farms, to provide support for pollinators and birds. It is not too late to adjust course. So lets think about what we can do to fix things.

Safeguard our natural heritage

This is a wide ranging topic that can be approached from many different angles. The main mechanisms for individuals are:

- Reduce our demand for natural resources

- Advocate to preserve and restore ecosystems

- Provide refuge for animals, plants and insects

Lets look at some specific intersections with helping protect and restore global biodiversity.

Note: I'm working on filling in each one of these. If you want to get the latest content as I write it, please subscribe!

- Luxury demand

- Biodiversity through food sourcing

- National parks and timber farming

- Micro-habitats and native gardens

- Pets

- Advocating for biodiversity

- Ecotourism

- Offsets

Ready for some inspiration? Me too. Let's take a look at one of our biggest disasters and how fast nature has bounced back.

Only 30 years. We could see it happen.