Big Bee

Mindset of Change

The Flight of the Bumble Bee by Jose Feliciano

The bee collects honey from flowers in such a way as to do the least damage or destruction to them, and he leaves them whole, undamaged and fresh, just as he found them.

St. Francis De Sales

When trying to live as a responsible human on this planet, it is inevitable that we make mistakes. After all, we humans are a relatively young species. Our lifetimes are short and we have much to learn in a mere 100 years (if we're lucky). When trying to navigate everyday choices – balancing considerations of cost, convenience, sustainability, greenwashing, taste, health and a myriad other criteria – it is easy to choose wrong.

I made such a mistake recently.

While traveling with family in the OP WA, we stopped at a local dry goods and produce store, and I purchased this honey. I was traveling with my sister in law, who has a PhD in Entomology and studies bee conservation. We've had many a discussion on the topic. Consequently I'm probably more broadly knowledgeable about bee problems than the average person. Yet, I was led astray.

Local. Raw. Wild. The jar certainly had the right buzzwords (hehe) to appeal to my susty soul. Local is almost always preferable in terms of food production. Raw speaks to the holistic health and wellness part of my brain, and wild soothed the inkling of wrongness that accompanies the idea of farmed animals in my mind. Sustainability is complex enough that its easy to form such heuristics. And marketing is very good at taking advantage of them.

The problem is: Only honey bees produce the honey that humans eat, and honey bees are not native to the United States.

Apis mellifera, commonly known as the honey bee, is native to Eurasia and was introduced to North America by immigrants. Honey bees differ from native North American bees in several key ways:

- Honey bees form hives, whereas most native bee species are solitary. This is important because a single hive can consume the resources that would support 100,000 native solitary bees (xerces.org).

- Honey bees did not evolve with native North American flower species, which means they are not as effective at pollinating these flower species as their native cousins.

- Honey bees are more opportunistic than native bees; they are not as discriminating about which flowers they cultivate from. Where native bees tend to prefer native plants, honey bees may prefer invasive species (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

- Honey bees host diseases to which native North American bee species are especially susceptible. They are often also genetically modified to resist these diseases, where as native bees have no such advantage (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Altogether, this means that honey bees are able to outcompete native bee species. This has caused a decline not only in native bee species, but in native plant species, themselves under pressure from invasive plants (naturalareas.org). This can have further knock on effects for insects like butterflies, who also rely on native plants.

All of which to say: By buying honey that was explicitly labeled as 'wild' and which, on further inspection, proudly touted the bees foraging on wild plant species, I was supporting an apiary operation that was explicitly encouraging honey bees to compete with native bees by taking the natural wild resources that native bees rely on (and which honey bees do not strictly require).

Ultimately, not the most sustainable option. I was sad at having supported the decline of native bees, and I decided to write this post to offset my failure. May you avoid such a mistake! (The honey was still delicious.)

Now, you might be wondering, what else are the honey bees supposed to do, if not forage for pollen on wild plants?

Big Bee

Honey bees are big business. As native bee populations have continued to decline, honey bees play a key role in monocrop agriculture as pollinators. By definition, monocrop farming is planting the same crop over and over again on the same land. [By contrast, regenerative agriculture rotates crops and/or sows complementary crops side by side, which both lets the soil regenerate and spreads out harvesting cycles.]

As monocrop farming has dominated huge tracts of land across the US, it has had an unintended side effect: severely reducing the food sources for bees. Bees need to forage over a large part of the year in order to gather enough pollen to withstand winter. This is true for both native bees and honey bees. But with monocrops dominating the landscape, all the available plants flower at the same time, requiring pollination for a few weeks of the year, and then leaving the landscape empty of flowers. Bees cannot naturally survive this way; there is nothing for them to eat the rest of the year.

Big Bee has stepped in to solve this problem for Big Ag, by shipping colonies of honey bees around the US to pollinate crops for the few weeks they are needed (ers.usda.gov). These honey bees are rotated throughout the US until the hive has produced a sufficient amount of honey and would normally go dormant. Then they are robbed of their honey and beeswax, kept alive with corn syrup or other subpar food sources (often byproducts of monocrop corn production), and the cycle continues.

Of course, by interrupting their foraging cycles, and then stealing their honey and beeswax, Big Bee also weakens honey bee colonies, making them more susceptible to disease and parasites, which they may then pass on to their native brethren (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), worsening the problem (peta.org). In the United States, honey bees are considered livestock (avma.org), and we tend to treat them as such - which is to say, not very well.

Of course, this cycle has hit native bees even harder. Not only are their native habitats destroyed to make room for monocrop farms, but they have to compete with the honey bees during the one time of the year when resources are plentiful. And on top of that, they might catch a disease or parasite from the invaders.

Plus, we haven't even discussed pesticides. Monocrop farming tends to go hand in hand with heavy pesticide use (ucdavis.edu). Researchers have characterized using honey bees as temporary pollinators "like sending bees to war" due to the high mortality rate (theguardian.com). This weakens honey bee populations even further, making them even more vulnerable to spreadable diseases, and can prove deadly for honey and native bee alike.

If you're feeling sad for the bees, then you are beginning to understand the complexities of the situation. On a deeper look into the Olympic Wilderness Apiary - from whom I bought my local raw wild honey - I discovered yet more nuance.

The Olympic Wilderness Apiary (OWA) has been operating since 1985 as a small local apiary. However, they were familiar with local populations of 'wild' honey bees - that is to say, unmanaged honey bee colonies that escaped from early settlers and had been existing in the wild for decades. In 1995, when the USDA Honeybee Stock Breeding center put out a call for 'wild swarm' queens to help save the US honey bee populations from decimation by the varroa mite, a virulent parasite, the OWA was able to help. They have since become a valuable resource for monitoring honey bee populations in the wild, and for maintaining hardy populations.

Of course, while this may be encouraging news for the honey bees - there might actually be a better and more ethical way to treat our pollinating livestock - it doesn't do much for the native bees. Honey bees are still competing with the native bees, who play a valuable role in maintaining native ecosystems.

So, what does this mean for us humans who are trying to live responsibly?

A few takeaways:

- At the end of the day, honey is not a very sustainable product. Consider swapping it out for real maple syrup or agave syrup (although, as always, be careful about sourcing), or just eat less honey. If you are going to buy it, sourcing it from responsible local apiaries is probably the best bet. At least then you aren't supporting Big Bee and the host of problems that accompany monocrop farming.

- Of course, from a sustainability perspective, its best if those local apiaries are providing their own bee foraging landscape (ideally, by planting native plants) to support their bee populations, and not encroach on native bee habitats. And for those concerned about health, the old myth that honey from local sources helps with allergies is unsubstantiated by science (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

- Compensate for your honey eating by planting a native pollinator garden! Supporting native bee species can be as simple as planting a flower garden. Just make sure you are planting species native to your region, and ideally, plant species that bloom at different times of the year to support healthy native bee populations (fws.gov).

- Learn how to identify different bee species and contribute to their conservation with citizen science! Many states have specialized programs, so look for one in your area!

- Look out for bee-washing, and help educate others on the importance of native bee populations and ethical honey bee cultivation.

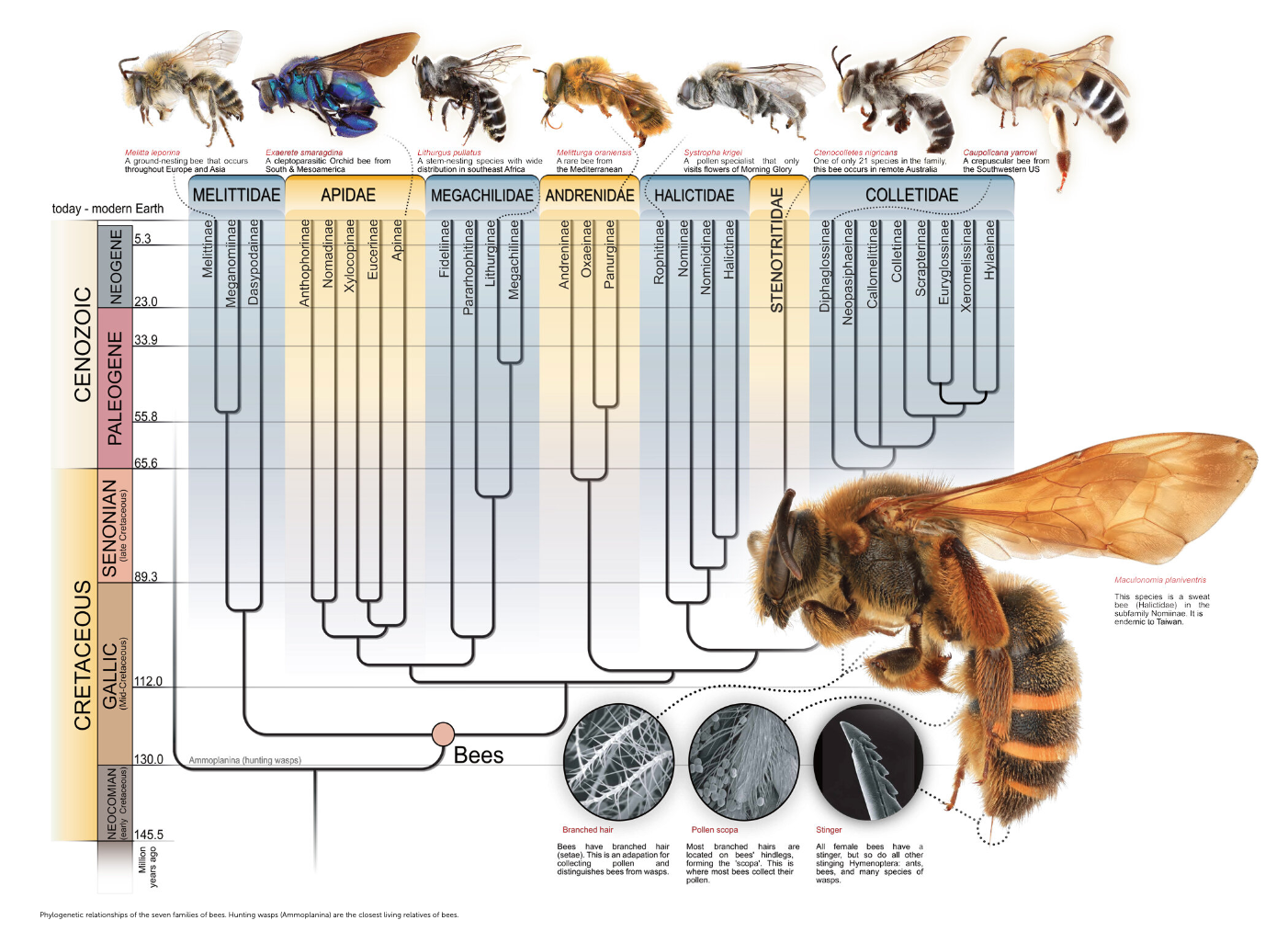

Living sustainably is a journey, and we all make mistakes. After all, we humans evolved only around 300,000 years ago. We are a young species next to the bees, who evolved 120 million years ago!

We have much to learn from our bee brethren, who have played critical roles in ecosystem health for far longer than our species has existed, and on whom we still rely for food production. There are an estimated 20,000 species of bees in the world, and 4,000 are native to the United States (usgs.gov). Solitary and hive-oriented, specialized and undiscriminating, scary and adorable, let's make sure the bees survive to teach us more in the future.

Remember: It's impossible to be perfect, but it's easy to do better. Keep on keeping on!

An extremely cute bee doing the only appropriate kind of bee-washing: