(Eat less) Meat

Mindset of Change

Beef Rap by MF Doom

"Understand, when you eat meat, that something did die. You have an obligation to value it - not just the sirloin but also all those wonderful tough little bits."

Anthony Bourdain

Meat fundamentally requires the taking of a life - that of a fish, mammal, bird, reptile, shellfish or insect. (In fact, there's probably not a single creature on this planet that we haven't tried eating.) In the best case scenario, this creature has spent its life happily gamboling around in its natural habitat (or in a close approximation thereof), is killed quickly and mercifully, and its corpse respectfully and completely used to provide nourishment or useful materials to other creatures, plants or the soil. This is how most indigenous peoples, and all our ancestors, approached meat for centuries.

Even in cultures where meat eating is currently entrenched in modern life, history often tells a different story. For example, in Japan (home of Kobe beef and wagyu) meat eating, and beef in particular, was banned for centuries due to religious beliefs (atlasobscura.com). In fact, in many ancient cultures, the killing of animals was only done in the context of sacrifice - with ritual and respect.

'Christians liked to quote a local Bible teacher: “What use are the ancestor spirits? They just use up chickens.” For their part, marapu people would point out that they only kill animals for ritual purposes, and never without an offering prayer to direct the sacrifice to its goal. By contrast, they would say, “Christians kill with no words. They are greedy, slaughtering animals whenever they feel like it, just so they can eat meat.”'

Webb Keane, 2018 (recollections of cultural differences between native Indonesians - marapu - and western Christian immigrants) (aotcpress.com)

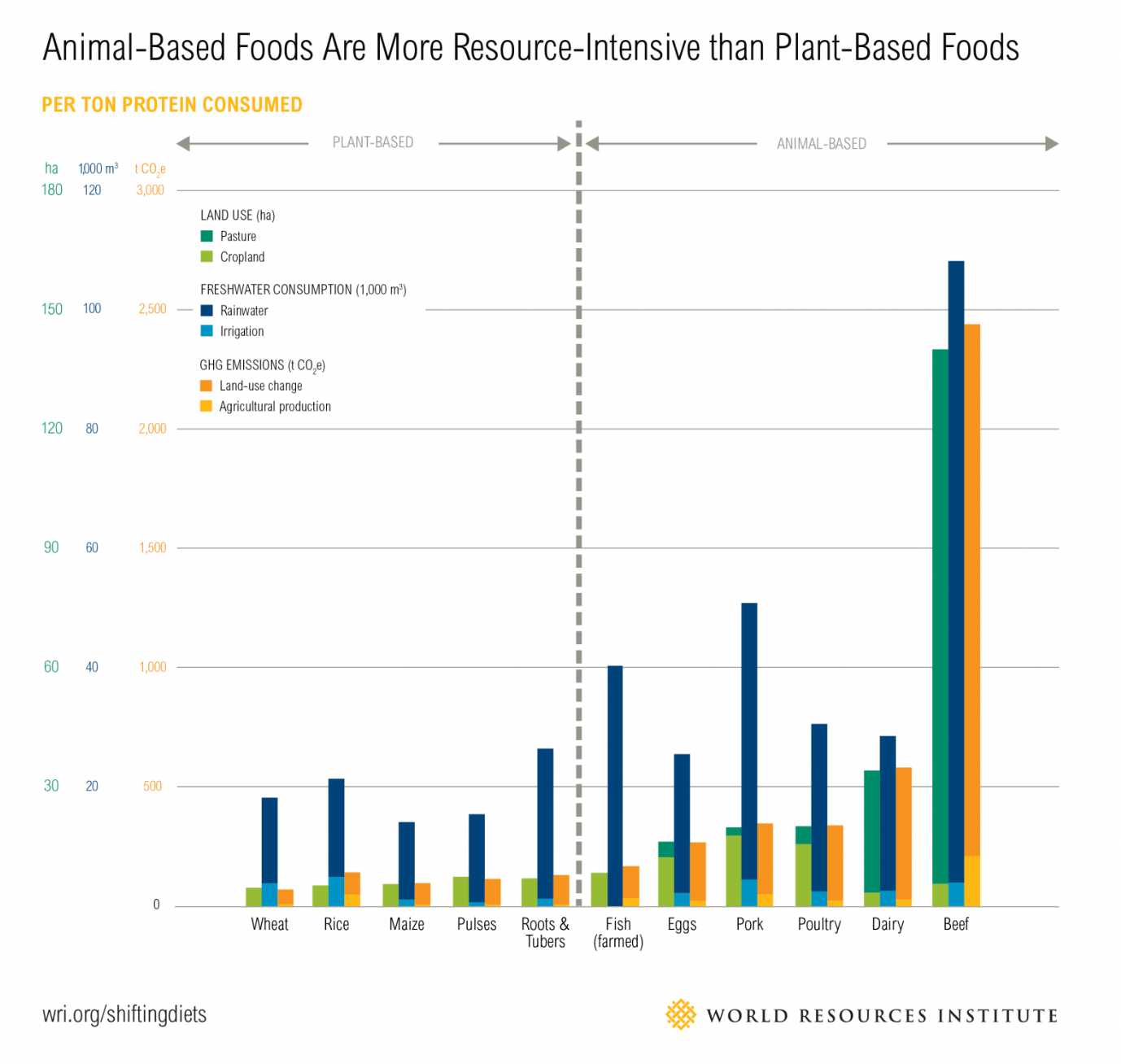

Reckless killing of animals was something done only by the spoiled rich or impious. It was also uneconomical. Raising animals is much more resource intensive than farming plants in terms of water, land, and carbon emissions. In order for a land mass to feed people at scale - say a tiny island nation in the 18th century or an Earth in the 21st - these can be real constraints. Modern intensive farming largely ignores these constraints. Partially due to technological advancements, but also because the short term monetary costs of using water, emitting greenhouse gases, and destroying native habitats are low, even if the ultimate cost is high (themedicon.com).

Animal husbandry > production

Its important to recognize the shift from animal husbandry to meat production (foodsystemsprimer.org). When you have raised an animal from birth, seen it grow, maybe even named it, you do not kill so easily. Of course, traditional farmers and ranchers are no strangers to slaughtering for meat, but they tend to have more respect for the creatures they live next to. The same goes for hunters, many of whom have been hunting for decades, have spent time with the animals in their natural habitat and learned their behaviors, have watched generations come and go. When you have seen babies grow into adults and have offspring of their own, you become a witness to the cycle of life. Seeing animals behave like animals, you develop empathy and perspective.

By contrast, industrial animal agriculture has objectified animals into meat. In particular, as in many industries, separating the consideration of profit and scale from the cost and process of producing the thing - in this case, raising animals - has cause a whole host of sustainability, health and ethics issues.

"The FAO has calculated that 70% of all antibiotics produced around the world are administered to livestock. They are also fed hormones in huge quantities because the animals have to become “profitable” as soon, and as often as possible. They have to be fattened and able to reproduce extremely quickly. To give an example: in the natural world, cows can live up to 20 years and produce seven calves; those farmed intensively have to produce a calf every year, and live five years at most, by which time they are exhausted, so they are slaughtered." (themedicon.com)

This disconnect should be no surprise, given that intensive factory animal farming has become big business.

“Our leading agricultural colleges still churn out "business-focused" young farmers, fired up with productive zeal. Students are taught to be at the cutting edge of the new farming, applying science and technology to control nature. They are taught to think about the land like economists. They are taught nothing about tradition, community, or ecological limits. Rachel Carson isn't on the curriculum. Different colleges and courses elsewhere churn out young ecologists who know nothing about farming or rural lives. Education is divided by specialism, and sorts the young people into two separate tribes who can barely understand each other.”

James Rebanks (regenerative farmer), Pastoral Song

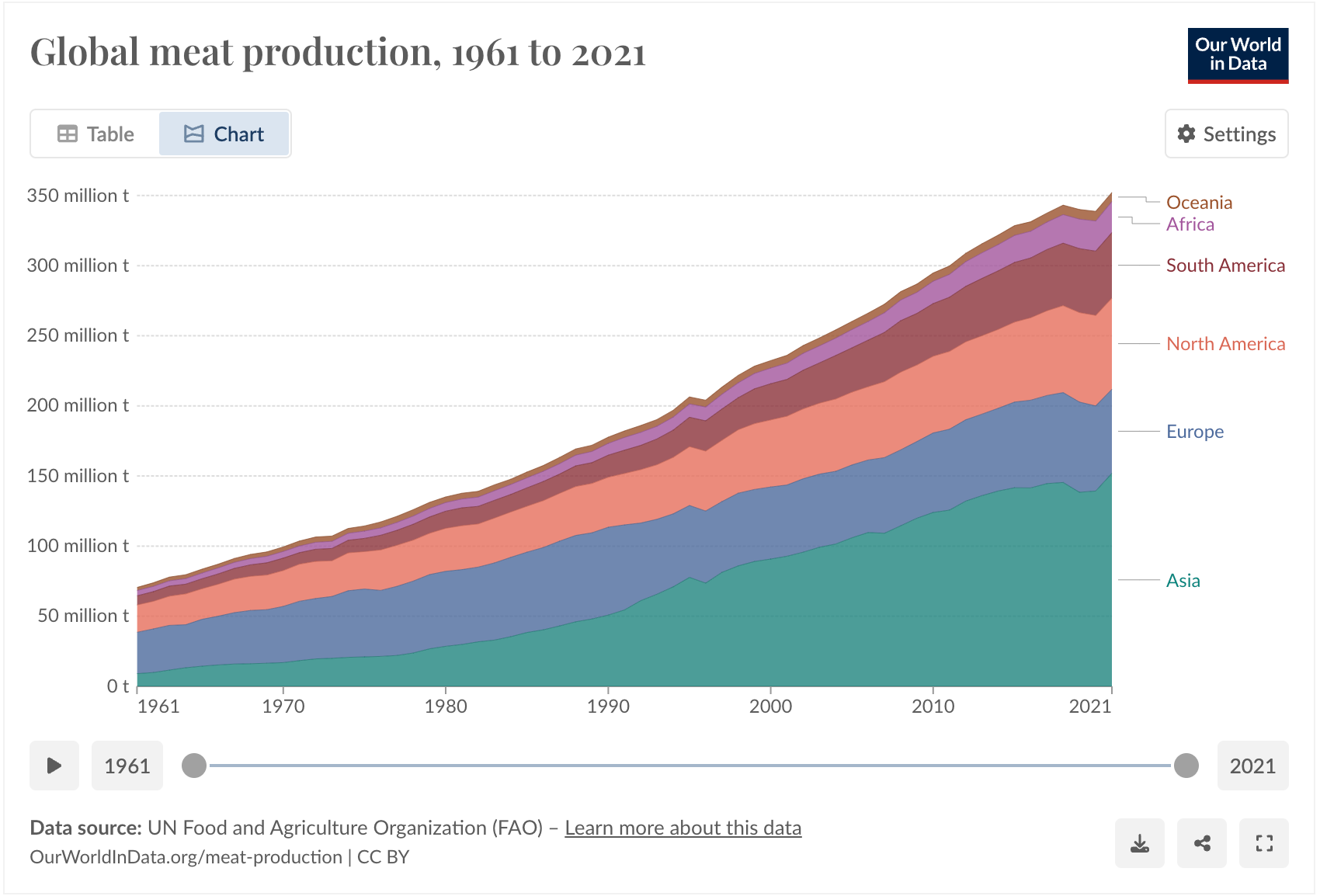

As consumers, we are further removed from the realities of what it takes to have meat, to the point where children often have no idea where meat even comes from (sciencedirect.com). By the time these children become adults, they may have learned some of the harsh realities, but it's become rare to experience animals in nature and rarer still to experience their lives in intensive animal farms, or to be confronted with their deaths. We can have meat without seeing or internalizing the cost in any real way. It should be no surprise that global demand for meat has risen. Since 1961, production of meat has quadrupled (ourworldindata.com). And not only has individual demand for meat risen, but the number of people who demand it has also increased.

Meat as luxury

In the last 30 years or so, over 700 million people have been raised out of extreme poverty (worldvision.org). As these people gain wealth, they naturally want to experience more luxuries, including eating more meat. This is particularly true in Asia, where production of meat has increased 15-fold since 1961.

Western influence has certainly played a big role in converting many traditionally vegetarian cultures into avid meat eaters. In Japan, this was done quite explicitly: "Although beef is a wonderfully nutritious food, there are still a great number of people barring our attempt at westernization by clinging to conventional customs...Such action is contrary to the wishes of the Emperor.” (atlasobscura.com). In fact, Westernization has radically shifted many of the food systems across Asia, introducing more processed food as well as more wheat products and meat (fao.org).

Despite the Japanese emperor's opinion on the health benefits of beef, eating a lot of meat, red meat in particular, is not terribly good for you (mayoclinic.org). This may be one reason why, although an increase in income is correlated with eating more meat, at a certain point it begins to taper off (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). In other words, although the newly middle class may want to eat more meat, the wealthy eat less. This doesn't even consider the long term use of antibiotics, which builds bacterial resistance (healthline.com).

The other odd thing about meat as luxury is that luxury is traditionally associated with rarity. Luxury items lose their value and their quality when they become too accessible. When meat was available only on feast days or during celebrations, it was special, something tasty and rich, to be anticipated - the proverbial fatted calf. Having it every day makes you less likely to appreciate its cost, as well as its quality.

Eat less meat

By this point, it should be clear that eating less meat has a host of benefits. It's better for the planet. It's better for you. It represents more respect for the animal. It's more in line with the wisdom of our ancestors. Plus, its cheaper.

Although Impossible and Beyond meat are more expensive than beef, plant-based diets in general are much cheaper than meat-intensive diets (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). And if the US didn't subsidize the meat and diary industries to the tune of $38 billion a year, the cost of a pound of hamburger would be $30 instead of $5 (aier.org). In that case, even Impossible meat would be much more accessible.

Story time. I was raised vegetarian. I liked meat, but because my mom was a vegetarian and refused to buy or cook it, we rarely had it at home. We only ate meat on special occasions - during holidays with family or when we celebrated birthdays by going out to eat. By the time I became an adult, I had seen Food Inc. and was a vegetarian for several years. Then I discovered fine dining and became an inveterate foodie. As a foodie, it is very difficult not to eat any meat. But you do gain a much greater appreciation for innovation and sourcing.

Having as much meat as you want, in any cut you want, does not yield innovation. Take a steak, for example. The taste of a steak is most dependent on the quality of the meat itself, which depends on the cow and getting the best cut. Generally speaking, this means sourcing expensive high quality beef. Of course steak is delicious, but to only eat steak (or chicken breast or pork chops) is a missed opportunity. By contrast, some of the greatest cuisines in the world have figured out how to convert cuts like ox tail, beef cheek, pork shoulder, or chicken thighs into delicacies. Creativity comes from constraint.

So I guess what I'm saying is that, in addition to all the other reasons to eat less meat, it makes for better eating.

Eat meat better

When I think about eating meat, a few primary objectives come to mind:

- Eat better meat. That is to say, source your meat better. Look for local farms, CSAs, or butchers who have high standards and only source sustainable pasture raised animals. Or if buying from a grocery store, find one that has established high standards for meat and fish. I find that Whole Foods does the best job at this among common super market chains. Of course, buying high quality meat is more expensive, but that is ok because we buy less of it. We have beans for cheap protein.

- Buy whole animal or less common cuts. Many farms and butchers will sell quarter, half or whole animals. This can be more expensive up front, but tends to be cheaper in the long run. It also gives you the opportunity to experiment with cuts you may be less familiar with, and its better for the farmer and the animal. For example, the US obsession with chicken breast has caused a greater number of chickens to be killed and far less ethical and sustainable practices in raising chickens (bonappetit.com). If your freezer is too small, consider buying less common cuts. Ask the butcher for advice!

- Use it all. When I buy a rotisserie chicken, I get more than a week's worth of meals from it. First, I eat the chicken breast. Then, I pick the scraps off the chicken, reserving the dark meat for use in pasta, quesadillas or sandwiches. I make stock from the bones. Skin and fat can be used to make schmaltz. This usually feeds two people for over a week.

Now, there are a lot of confusing standards for meat so here is a pretty neat guide. I look for pasture raised, grass fed, and humanely raised - certified as such. Or, I try to find a small transparent local farm that is open to visitors, where I can check the animal conditions myself.

Organic is preferable but it can be very expensive to get organic certified, and there are many small farms that can't afford it. I prioritize small local farms with a generally good approach over larger organic industrial farms. I also trust my CSA and Whole Foods, having done the research to vet their standards ahead of time, but I do try to look up new brands I haven't seen before. Its up to you what level of quality you feel comfortable with. It can be tricky to balance cost, ethics and sustainability.

The goal should be to really appreciate the meat that we eat by supporting sustainable and ethical foods systems. I feel that if I am not willing to put in the effort to source well or figure out how to cook an unusual cut, then I am not treating the animal with respect. I prefer to not eat meat when I'm feeling like that. By really confronting the nature of what it means to eat meat, I naturally begin to eat less.

How to eat less meat

Clarity of intention and motivation is very important when trying to change any behavior. We need to be really honest with ourselves about what we are trying to do and why. In particular, for many people eating meat is part of their identity (sciencedirect.com), whether its because they perceive meat eating to be manly or healthy, a sign of status, or they simply value the camaraderie and tradition of the family BBQ. Trying to change habits around eating meat can feel like an assault on that identity. Ethical (some would say moral) considerations can add fuel to the fire. Most people do not react well to feeling guilty or under attack. They are not good conditions for behavior change. At the same time, most people are rational and can acknowledge the harsh realities of killing animals and the problems around sustainability. It's not really a question of reason, but of emotion.

So a couple reminders. Sustainable habits have to be sustainable for you. You don't have to do anything. You are choosing to do something. And heck sometimes eating less meat doesn't really mean eating less - just eating differently.

So let's consider some options:

- Source better meat (e.g. buy higher quality from better farms)

- Eat less meat in a week (a la Meatless Mondays)

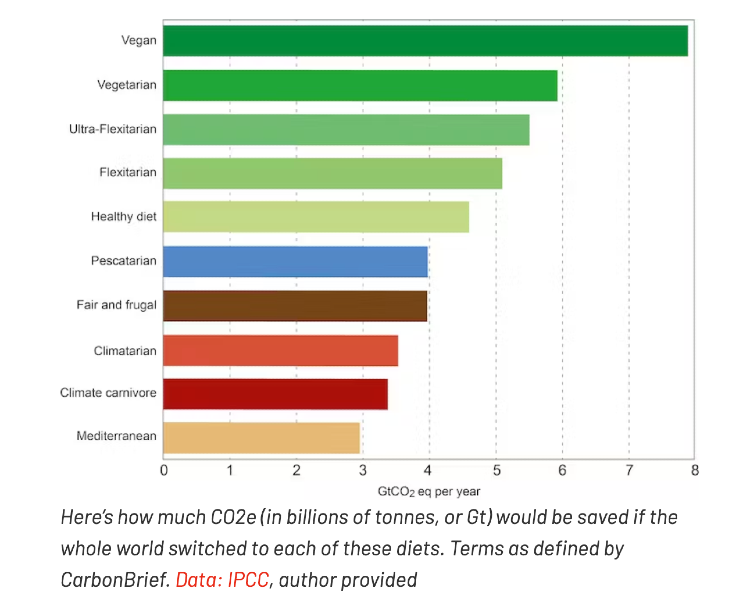

- Choose better types of meat (opt for fish or chicken over beef)

- Use it better (make the most of the meat that you eat)

- Choose better cuts or whole animal (talk to your butcher!)

This can be a lot to do at once, so maybe start with one or two things. And if you are just rarin' to go, then here are some more options to explore. I'm shooting for ethical flexitarian myself.

Here's my handy checklist for getting started:

- Think about your relationship with meat. Be honest with yourself about what it means to you, how you've thought about it before this and how you really feel now.

- Think about what's realistic for you. Maybe you have family members who are die-hard meat eaters (send them this post?) or maybe you have health concerns? Or maybe budget is a big concern. Food can be tricky for a lot of people.

- Do some research. Maybe look up a CSA or local farm. Maybe price out your budget if you bought higher quality or bought less. Maybe look up some tofu recipes or think about alternative protein sources.

- Decide on a period of time to try it out. Maybe a week or a month. No need to be overly ambitious. Commit to something you're confident about. You can't always do more later.

- Talk to the people who might be affected. Perhaps a partner or roommate, friends who eat meat a lot. Think about how you want to approach social situations. There's no right or wrong way, but you can decide how you want it to go.

- Don't be afraid to make mistakes. Social situations, having a bad day, being on the road, pressed for time, strong cravings can overwhelm good intentions. So you had a burger or some chicken nuggets. It's not the end of the world. The pattern is greater than the instance. Start again.

- Reflect on what's worked and what hasn't. Think about what you would do differently. Be honest about why you didn't like something. Think about why something did work for you and carry that forward. You're adaptable!

Overall, just remember that something is better than nothing. We are all just doing the best that we can.

Here's a little inspiration from Gentleman Farmer James Rebanks:

If you want a new vision for the way humans can treat animals in farm settings, check out his books. They're easy reads and very insightful and inspiring.